The life of an exotic trader often involves selling cheap calls and buying expensive puts. A strategy to make the put more expensive and the call cheaper is to write options not on a single equity, nor on a basket of equities, but on the worst-performing of, say, three equities.

The human mind struggles to properly conceptualize the distribution of the worst of three assets. While we can easily imagine the worst-case scenario for an individual stock, envisioning what a ‘bad scenario’ looks like for the worst-performing among multiple stocks is far trickier. That participates in making the worst of a popular solution amongst investors.

As a result, exotic traders are effectively short worst-of forwards, which means they are not merely short correlation—they are ???????????????????? ????????????????????????????????????????. This distinction is ????????????????????????????. Being short correlation carries well if sold at a premium versus realised, and at the end of the day the realised correlation cannot go over 100%! However, being short covariance is different; when it goes wrong, the potential losses are not capped.

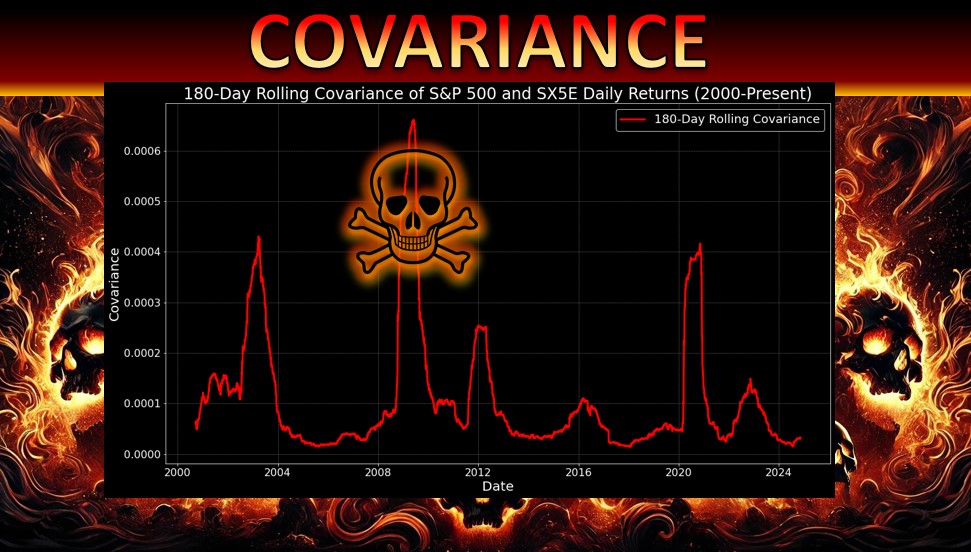

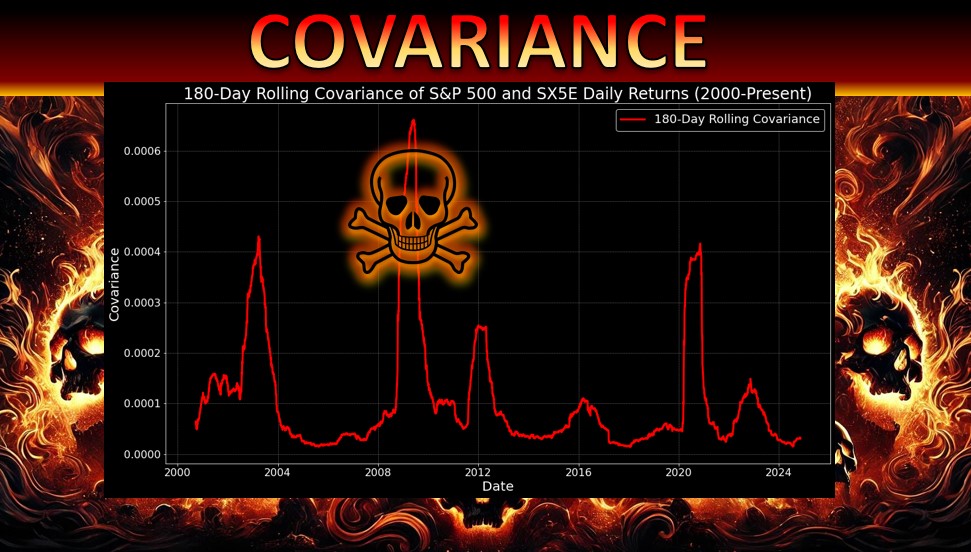

Anyone who has traded an exotic book knows the difference ????????????????????????????????????????. Those who navigated the 2008 financial crisis can vividly recall the steep cost of being short covariance. The covariance between equities reached exceptional levels (see graph with SPX-SX5E covariance). At the time, Deutsche Bank, then a major player in equity derivatives, reported losses of €1.7 billion in its exotic books, largely driven by exposure to short covariance risk. Société Générale faced a €500 million loss in Q4 alone due to similar positions. BNP Paribas, another key dealer, posted nearly €2 billion in losses in its equity derivatives business that year, highlighting the potential devastating impact of a short covariance position.